Trump's coronavirus national emergency declaration, briefly explained.

It's a declaration that guarantees a boost of funding to the states.

President Donald Trump just declared a national emergency, in response to the novel coronavirus outbreak the US is facing.

This act will free up federal funding for the states to use in response to the crisis, enabling them to tap into $42.6 billion that could be applied to tests, medical facilities, and other supplies.

The emergency declaration falls under the Stafford Act, which governs the federal response to public health and natural disasters. It was previously used in a similar capacity by President Bill Clinton to address an outbreak of West Nile virus in New York and New Jersey in 2000.

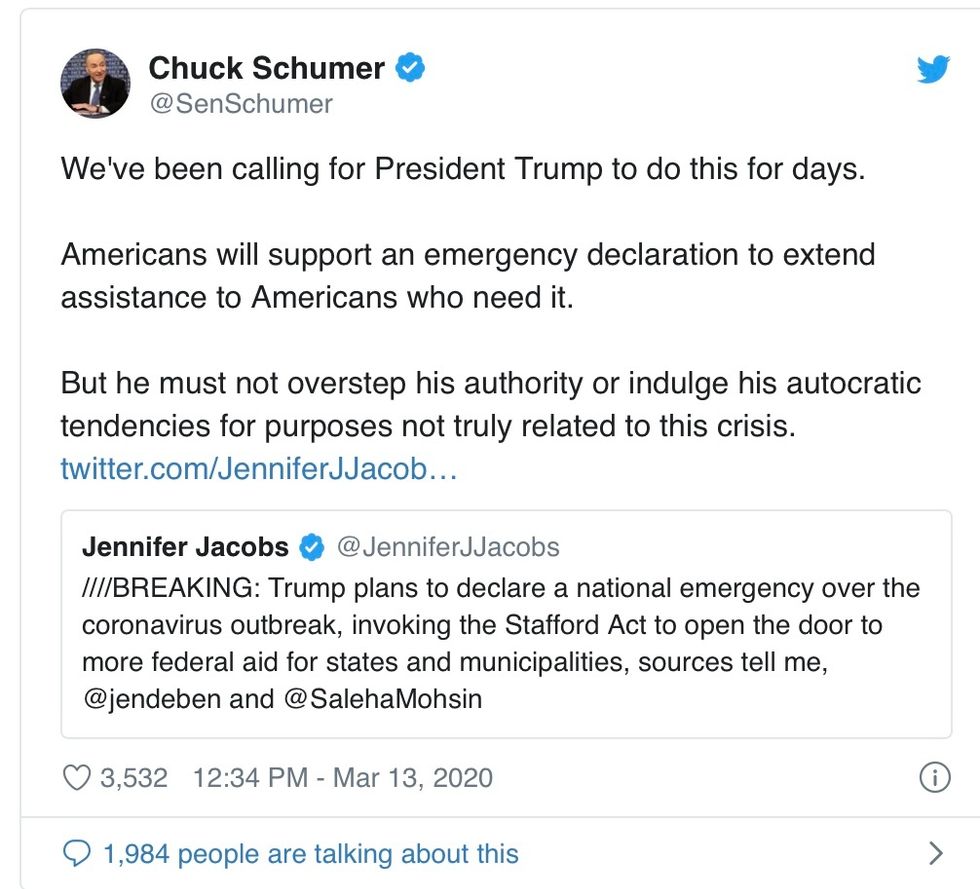

Senate Democrats earlier this week urged Trump to consider this option as state and local governments scramble to address the influx of patients who need tests, and potential medical care. The number of confirmed Covid-19 cases in the United States continues to climb, according to Johns Hopkins University.

Given how contagious the virus is — experts estimate that hundreds of thousands of people could contract it in the coming months — the strain on medical systems across the country is only expected to grow.

Trump's decision to declare this emergency is significant: It will increase the resources that states can access as they grapple with the demand for medical care and assistance, and it highlights at least some acknowledgment from the president regarding the severity of the coronavirus outbreak — a stark turnaround from his past attempts to downplay it.

What the emergency declaration will do

The biggest impact of this declaration is that it will give states a boost in funding to address the need to pay more medical staff, bolster facilities, and treat patients. Under the Stafford Act, which was passed in 1988, once a president declares an emergency, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) is able to funnel money from its $42 billion disaster fund to various state governments.

"This federal funding could bolster states and localities that are impacted by novel coronavirus which the World Health Organization has proclaimed a pandemic," Stetson University Law Professor Ciara Torres-Spelliscy tells Vox.

According to the letter Senate Democrats sent the administration earlier this week, this declaration means that the federal government will cover 75 percent of cost sharing with states for specific resources related to coronavirus response including medical equipment and vaccines.

These emergency declarations have typically been prompted by requests by state governors — as outlined by the law, but the president can act sans this request "where necessary to save lives, prevent human suffering, or mitigate severe damage," according to The Brennan Center's Liza Goitein.

This emergency declaration is expected to be different from the one that Trump made last year to obtain funding for a wall along the southern border. That action was taken under the National Emergencies Act, which also enables the president to do things like seize control of the internet.

The Stafford Act, meanwhile, is specifically designed to outline the government's coordination with state and local governments in the instance of potential public health and natural disasters.

As Reuters points out, this declaration is also distinct from the one made by the Department of Health and Human Services earlier this year. The agency had previously deemed the rise in cases of coronavirus a public health emergency, which enabled the administration to impose travel restrictions on those who have visited China.

The Stafford Act was previously used to address West Nile

This declaration is not the first time that Trump has invoked the Stafford Act. He also used it in the case of wildfires in California and hurricane damage in Florida, in order to organize the federal response in both of those situations and provide states with extra financial support.

"These statutes are invoked quite often, several times a year," Princeton University political science professor Keith Whittington tells Vox. "Just a few days ago, the president invoked this authority to assist Tennessee after a significant tornado."

The Stafford Act has been used in the past to respond to a medical disaster, too: Clinton made an emergency declaration in 2000 to respond to the spread of the West Nile virus in two states. At the time, the federal government was able to send up to $5 million in federal money in order to support mosquito control efforts.

President Barack Obama also used the National Emergencies Act to declare a national emergency to address the swine flu outbreak in 2009. This decision enabled the federal government to help shape the medical response, and allowed hospitals to treat swine flu patients at separate sites, for example.

The decision to use the Stafford Act again is just one step the government can take in its coronavirus response. Congress is also weighing legislation to address paid sick leave and guarantee free tests for people regardless of whether they are insured.

Li Zhou | March 13, 2020 3:34 pm, Vox

###

March 13, 2020

Voices4America Post Script. Senate Dems have been urging Trump to declare a National State of Emergency for sometime. Trump finally acted. It was 13 days ago that Trump last called the #coronavirus a Dem hoax. #NeverForget Now let's see if the #WorstPresidentInHistory can execute.

Sample. The Golden State received test kits for COVID-19 from the federal government that did not include all the components needed to actually run a test.

https://www.huffpost.com/entry/california-coronavi...

Here is the New York Times update on what the National Emergency, or, as Trump says, two big words, means.

After missteps, the Trump administration refocuses on testing.The Trump administration moved on Friday to drastically speed up coronavirus testing, rushing to catch up with surging demand for tests.

The government gave the Swiss health care giant Roche emergency permission to sell its three-and-a-half hour test to U.S. labs, and said it was awarding over a million dollars to two companies to accelerate development of one-hour tests.

Testing has lagged in the country, infuriating the public, local leaders and members of Congress. Sick people across the country say they are being denied tests.Administration officials have promised repeatedly that enormous numbers of tests would soon be available, only to have the reality fall far short.

"I don't take responsibility at all," President Trump said in response to a reporter's question on Friday, "because we were given a set of circumstances and we were given rules regulations and specifications from a different time."

While South Korea is testing 10,000 people a day,overall U.S. state and federal testing has yet to log even 15,000, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Speaker Nancy Pelosi highlighted the urgency on Friday, while discussing an emergency spending package she said the House would pass later in the day, saying, "The three most important parts of this bill are testing, testing, testing."The Department of Health and Human Services on Friday assigned an assistant secretary, Adm. Brett P. Giroir, to oversee testing efforts. A day earlier, in a congressional hearing, top health officials were unable to say who was in charge of making sure that people who needed tests got them.

One of them, Dr. Anthony S. Fauci, finally responded: "The system does not, is not really geared to what we need right now, what you are asking for. That is a failing. It is a failing, let's admit it."

"The idea of anybody getting it, easily, the way people in other countries are doing it, we are not set up for that," Dr. Fauci added. "Do I think we should be? Yes. But we are not."