They're registering voters. They're spotlighting the work of local organizers. They're talking about all forms of gun violence.

Six months and a day after a gunman massacred 17 of their classmates and staff, the students of Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School woke up Wednesday and began a new year.

For the past two months, a busload of them have traveled the country in pursuit of stricter gun laws, connecting with local activists, holding rallies, debating counterprotesters and, above all, registering voters.

They knew perfectly well how many before them — after Columbine, after Sandy Hook, after Orlando — had been unable to turn outrage into lasting change. But this time was different. Since the shooting, state legislatures have passed at least 50 gun regulations, largely because of public pressure created by the Parkland movement. So The New York Times spent three days on the road with the March for Our Lives activists to find out what changed.

AUG. 1: GREENSBORO, N.C.

It's not about banning guns

They started the day where the sit-ins began nearly 60 years ago, at a Woolworth's lunch counter pristinely preserved within the International Civil Rights Center and Museum.

Remember, said the museum's chief executive, John L. Swaine, the movement that would desegregate lunch counters across the South started with just four people — and they were your age.

From the sunny lobby, the students descended into the galleries. They saw the lunch counter. They saw a brick archway engraved with the words "COLORED ENTRANCE." They saw an image of Emmett Till's mutilated body.

At the end, they saw a wall covered in a mosaic of civil rights activists' faces. Here and there were blank spaces. "We left them open for you," said their tour guide, Dillon Tyler.It was, he said, his "true honor" to give them this tour — because 12 years ago, it was his school that was shot up.

Mr. Tyler, now 26, was a freshman at Orange High School in Hillsborough, N.C., when a gunman came in 2006. Though no one was killed there, "we were trapped in that school for five hours," he said, his voice breaking. "Meanwhile, all you heard was bullets and screams."

The room was silent as he finished speaking. Then Sara Jado, 18, a member of March for Our Lives Greensboro, emerged from the crowd and hugged him. For more than 10 seconds, she did not let go.As Ms. Jado retreated, Emma González, 18, stepped forward. Then another student. And another. They didn't speak. They just opened their arms, and Mr. Tyler cried on their shoulders.

These are the bonds that linked everyone on this tour: trauma, and fear, and the knowledge that any of them could be next. Some fell asleep to the sound of gunfire as children in Chicago or Milwaukee. Now they were meeting with people who bore the scars of mass shootings more than a decade old. And they were joined by 15-year-olds who spoke casually about which classrooms had good escape routes, and which ones they were likely to die in.

"Let us have a childhood," Anne Joy Cahill-Swenson, a rising sophomore at Grimsley High School in Greensboro, told the crowd at LeBauer Park that evening. "This is not something we should have to worry about."

Across the street, a dozen or so counterprotesters with red MAGA caps, "I Plead the 2nd" posters and a QAnon signwere on the sidewalk, shouting at Matt Deitsch, a 2016 graduate of Stoneman Douglas and the chief strategist for March for Our Lives.

"Violence will happen if people try to take guns away from us," warned one of them, Jason Passmore, 33.

Mr. Deitsch, 20, has a seemingly endless supply of statistics, and he chooses his words carefully. "People define 'assault weapon' in entirely different ways," he said later. "People define 'gun control' in completely different ways. And for the most part, we've tried to back away from using those terms."

Sometimes this works. Ramon Contreras, 19, who founded Youth Over Guns after a friend was killed, recalled that at a tour stop in Texas, he and a counterprotester came "this close" to agreeing on the need for safe storage of firearms. They exchanged contact information and still talk.

Other times, it doesn't work.

"I love this country," Mr. Deitsch told the protesters in North Carolina at one point.

"Do you?" Nancy Browning said doubtfully.

But an interesting thing happens when you start talking. It turns out Ms. Browning, 45, supports closing a gun show loophole and banning bump stocks. And universal background checks? "Absolutely!" she said. "I don't think anybody should just be able to go get a gun."

"I just don't want them to come in and just want to completely blame guns for everything," she added. "The gun is not the problem."

Here lies the disconnect: the chasm between the policies March for Our Lives promotes and the policies many opponents think it promotes. The students don't want to abolish gun ownership. Some of their families own guns.

There is also an irony to the objection that they "blame guns for everything." They don't. At every stop, they emphasize that gun violence can't be addressed without addressing what fuels it: racism, poverty, substandard schools and mental health services. They speak daily about intersectionality, systems of oppression, the school-to-prison pipeline.

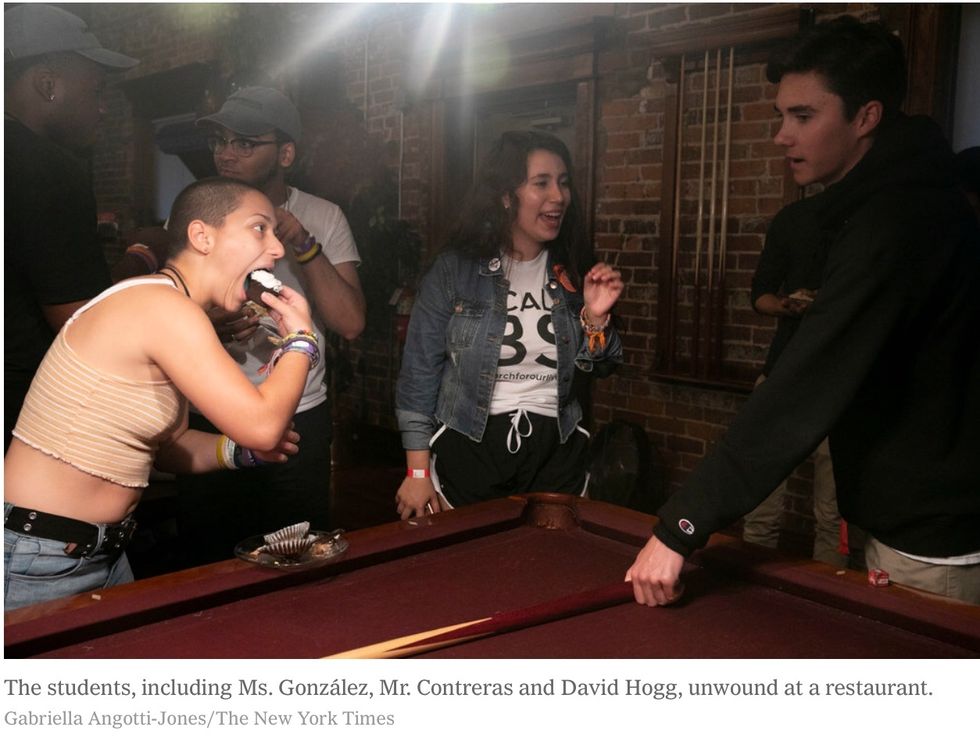

In fact, they talk about these things so much that it's easy to forget they are, well, teenagers. People who hold an impromptu dance party outside a theater when one of them starts banging out the "Pirates of the Caribbean" theme on a bright green piano. People who talk about prom and mock each other's pool shots and stuff cupcakes into their mouths whole.

——-

AUG. 2: BLACKSBURG, VA.

The movement is bigger than Parkland

Half an hour before the students' panel on Thursday, the line outside the Lyric Theater stretched so far that people in the back fretted they would be turned away.

Inside, the eight panelists assembled. Only two, Ryan Deitsch and Lauren Hogg, were Parkland students. The others were Mr. Contreras, from New York; Tallulah Costa and Louis Garcia, high schoolers in Roanoke, Va.; Matt Post, a recent high school graduate from Maryland; Geoffrey Preudhomme, of the Radford University Young Democrats; and Ryan Wesdock, of the Virginia Green Party.

It was as good an illustration as any of how the Parkland students wanted to organize the movement. They were adamant that it was not their movement. They understood that they wouldn't have such a platform if their town were not wealthy and mostly white — the sort of place where senseless violence is not "supposed" to happen.

"When we did the Peace March on the South Side of Chicago, they've been doing that for years — but all of a sudden, now that we showed up there, there were 10,000 people instead of 500," said David Hogg, 18. Last month, he added, he and the other students met a teenager in Oakland, Calif., who had lost 20 friends to gun violence, but Americans don't know their names.

This dynamic can be demoralizing for the people working without recognition. Bria Smith, 17, from Milwaukee, said she had spent a year working with local nonprofits and Black Lives Matter, but felt no one was listening. "Why would I do so much work and give so much energy of myself to a city that doesn't care if I'm doing it in the first place?" she asked.

Then she spoke at the March for Our Lives rally in Milwaukee, which led to a seat on a panel when the bus tour went there. Afterward, she recalled, an organizer asked if she wanted to join for more stops. (Her reply: "Give me a second. I have to call my mom and ask her first.")

Ms. Smith used to see Milwaukee as a prison to escape. But now, "I've met so many different youth who had wanted to make a difference in their communities, but never knew how to use their voice and their platform to do that," she said. "So after Road to Change, I'm going to come back, and I'm going to go to Milwaukee, and I'm going to be that voice for all the people who felt hopeless."

This is the biggest change of all. The students defined the problem itself differently, as gun violence writ large: not just mass shootings but gang killings, police brutality, domestic abuse, suicide. They talked about sharing their platform and using it to "raise the voices" of the activists who have been organizing in obscurity — several of whom, like Ms. Smith and Mr. Contreras, joined the tour. They tried to build infrastructure everywhere they went, coordinating with local people who would continue the work when the bus was gone.

Above all, they urged young people to vote. Many of their proposals already have widespread support. It's Congress and state legislatures, they say, that don't reflect the will of the people.

—

AUG. 3: CHARLOTTESVILLE, VA.

'Every single person that has died, I do it for them'

By 6 p.m. on Friday, Ms. González was lying on the floor of a back room at the Westminster Presbyterian Church, answering questions with her eyes closed.

She was getting a cold. Mr. Hogg, cross-legged next to her, was getting over one. At least two other students were sick, too. None of them were getting enough sleep.

Earlier, the students had met with Susan Bro, whose daughter, Heather Heyer, was killed here a year ago this week when a white supremacist drove into a crowd.

"Some of you may have experienced this — it's hard to get out of bed, because I can get weighed down in the grief," Ms. Bro, 61, told them. "And then I'm like, 'No, there's work to do.'"

The work is grueling. Jaclyn Corin, 17, contacted every local organizer before every event, and spent every day "going to events while organizing future events at the same time." Before the shooting, she had 100 contacts in her phone. Now, she has over 600.

"My texts never stop coming in," she said. "I will wake up at 2 o'clock in the morning in the middle of the night to get a drink of water, and I'll answer my five texts that I missed in those two hours that I was sleeping."

She and the rest of the students run the show. The handful of adults with them were there mainly to handle things that minors can't, like booking hotel rooms.

"We entirely control everything we do," Mr. Hogg said. "Anybody above 20 on the bus works for us."

This is exhausting. It's also empowering.

"I just remember being in those days and not immediately thinking I needed my parents' help," Ms. González said to Ms. Bro, recalling the week after the shooting. "It just was not our first instinct to get help from anybody except for ourselves."

Then, the students were galvanized by the friends they had just lost, and they were desperate to prevent more massacres. Six months later, they have a vastly broader view of the problems they want to fix, and a vastly longer list of people to fix them for.

Ms. Corin leapt in the day after the shooting because she had been on a dance team with one of the victims, Jaime Guttenberg. But now, she said, when she struggles to keep up the pace, she thinks of Philando Castile, too, and Michael Brown. She thinks of the young woman in Oakland who lost so many friends.

"This movement was started because of those 17, but it's become so much more than that," Ms. Corin said. "Every single place we go, I take those people's stories, their stories of loss and pain, and I carry them with me. And every single person that has died, I do it for them now."

New York Times, August 15, 2018. By Maggie Astor. Photographs by Gabriella Angotti-Jones.

###

August 16, 2018

Post Script. 'Every single person that has died, I do it for them.'

Share this. Register voters too. #MarchforOurLives

Do it for them!