Hal Singer was a toddler when a white mob descended on Tulsa's all-black community of Greenwood and burned his home to the ground.

Now 100 and ailing after a stroke, Singer, a renowned jazz band leader and saxophonist, is among the last survivors of the 1921 Tulsa race massacre, one of the worst episodes of racial violence in American history.

President Trump plans to hold a political rally in Tulsa on Saturday, which he delayed by a day after scheduling it on Juneteenth, the holiday that marks the end of slavery. The timing astonished historians and outraged African Americans.

The official records of Hal Singer's birth on Oct. 8, 1919, perished in the fires set by white mobs during the rampage, which left as many as 300 black people dead and more than 10,000 homeless.

"The only trace of my existence, aside from myself, could be found in the family Bible: one date written on the first page and a single name, Harold," Singer wrote in "Jazz Roads," his autobiography. "I was born. I am sure of the fact, since I am still living. But I never had the written proof."

The violence began unfolding on May 30, 1921, when a 19-year-old shoe shiner named Dick Rowland walked into the Drexel Building to use the only toilet in downtown Tulsa available to black people.

Rowland stepped into an elevator on the first floor. By the time the elevator doors opened on the third floor, someone heard the white elevator operator, Sarah Page, shriek. Rowland, who may have stepped on her foot, was arrested and accused of assaulting a white woman.

A crowd of white men gathered outside the courthouse, where Rowland was jailed. Dozens of black men, including World War I veterans, rushed to the courthouse to protect him.

"We all knew what would happen to the young man. Hanging was a certainty," Singer recalled his father telling him later. "Black families got involved and an important group of men organized a raid of the prison. They intended to free the man."

At the time, Greenwood was so affluent that it was nicknamed Black Wall Street.

"I don't call it the black part of town because in effect our section was an autonomous city in of itself: a perfectly structured community of about 30,000 people made up of three distinct neighborhoods," Singer recalled in his memoir. "We had our own churches, stores, athletic fields, services and even our own police force. A bus line crossed our town-within-a-town, and since it was run by one of our own, you could sit anywhere in the bus that you liked."

It was rare that black people had to go into the white areas of Tulsa. But his mother, Annie Mae Singer, who was a well-known cook in Tulsa, had a business catering in houses owned by white people.

Singer's mother later told him that during the 48 hours of the massacre, one of her white clients "courageously came to see us and drove my mother and me to the train station. She paid our passage to Kansas City and gave the conductor some money to protect us in case it was necessary."

Singer's father, Charles Edward, who oversaw a team of white workers at a mechanical tools company, stayed behind to fight as white mobs raged through their neighborhood.

When Singer, his mother and his siblings returned to Tulsa after the violence ended, Greenwood was gone.

The neighborhood where Hal was living was burned except for his church," said his wife, Arlette Singer. "The family had to build another house. It was awful."

Witnesses described bodies being dumped in mass graves. Nearly a century later, the city plans to dig in Oaklawn Cemetery to learn whether there is a mass grave there, though the timeline has been delayed by the pandemic.

Singer, who grew up playing violin as a child, attended Booker T. Washington, Tulsa's all-black high school. Then he began studying the clarinet and, while attending college at Hampton Institute in Virginia, the tenor saxophone. During a break from college, Singer was recruited to play with Terrence "T." Holder, a legendary Tulsa band leader and innovative trumpeter.

It was 1938. Singer was only 19. "I played the saxophone nights for a white audience with the famous T. Holder," Singer recalled in his autobiography. "I was very lucky. The only problem was that my friends couldn't come to hear me play because of segregation."

Eventually, Singer quit school to become a musician. He joined Jay McShann's orchestra in 1943 before moving to New York, where he found work in various bands, according to the Oklahoma Jazz Hall of Fame.

In 1948, Singer formed his own group and was signed to Mercury Records, where he cut his first single, "Fine as Wine." That year he recorded "Corn Bread," which reached No. 1 on the R&B charts, according to his discography. He followed "Corn Bread" with another hit, "Beef Stew."

Singer was recruited for the Duke Ellington Orchestra and played with Billie Holiday, Dizzy Gillespie and Ray Charles, among others.

After touring Europe with Earl "Fatha" Hines, Singer moved to France, where the minister of culture bestowed the title of "Chevalier des Arts" on him. He'd become increasingly disaffected with the United States because of its racial climate and oppression of African Americans.

"Finally, in 1965," Singer wrote, "I decided to leave my country because of the civil rights protests."

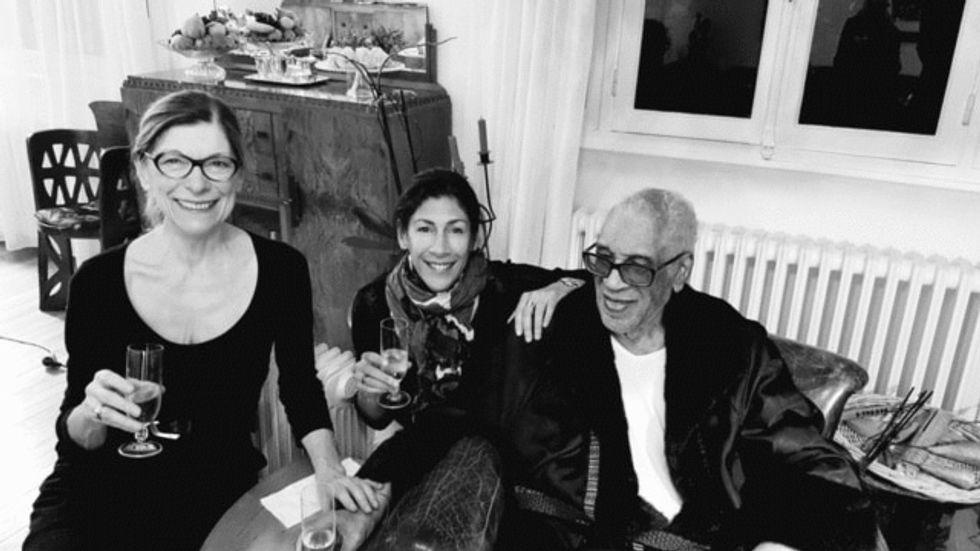

In Paris, he fell in love with Arlette, with whom he has two daughters. He continued releasing albums for decades and was honored by the Oklahoma Jazz Hall of Fame with a lifetime achievement award in 2013.

Singer has never forgotten Tulsa and what happened there, his wife said. But with his health failing, he wonders if there will ever be reparations for the lives lost and the properties destroyed.

I have no more trust in justice in my country," he told her. "It is too tiring. It is too ugly."

Read more Retropolis:

HBO's 'Watchmen' depicts a deadly Tulsa race massacre that was all too real

Washington Post, By DeNeen L. Brown June 19, 2020.

###

June 20, 2020

Voices4America Post Script.In 1921, white residents of Tulsa burned down Greenwood, the "black Wall Street," a thriving community- 300 dead, 10,000 homeless. This man was a toddler. Read and share. #TrumpRacistRally #TrumpdeadlyRally